Courtesy of Dan Noyes

- Dan Noyes is co-CEO of Tech Goes Home, a nonprofit that addresses digital inequities in Boston.

- He says he has a personal dedication to digital equity from his time working with middle schoolers.

- Since 2010, about 40,000 low-income residents have benefitted from TGH's programs.

- This article is part of a series focused on American cities building a better tomorrow called "Advancing Cities."

Dan Noyes, 45, has been working to close the digital divide in Boston for two decades.

His digital-equity work began when he was the director of technology for a Boston Public Schools high school. In 2006, he joined the Lilla G. Frederick Pilot Middle School in Dorchester to lead their one-on-one laptop initiative, where each student received a computer. But initially, the kids weren't allowed to take the devices home.

"What that meant was that this idea of trying to create lifelong learning, both in school and at home, was incredibly difficult because you've got this great tool in school, and then you go home and you didn't have anything," Noyes told Insider. "So we decided we needed to fix that."

The school invited parents and caregivers in for digital-literacy training on what their kids were learning, then the families received a computer. Noyes said the program then expanded to other schools.

In 2010, Noyes, who now lives just west of the city in Auburn, joined Tech Goes Home (TGH), a nonprofit founded in 2000 that addresses digital inequities across Boston through adult and family education, as co-CEO. He said his dedication to digital equity is personal, stemming from his middle-school students.

"I knew those kids and I knew those families," he said. "It was just so depressing to think that you had all these amazing students who had such incredible potential but one of the only things holding them back was resources at home. It's so unfair."

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the digital divide, as it forced students to learn from home and adults to work remotely. Noyes appreciates that the problem has received more awareness but said Boston (and the country as a whole) still has a lot of work to do.

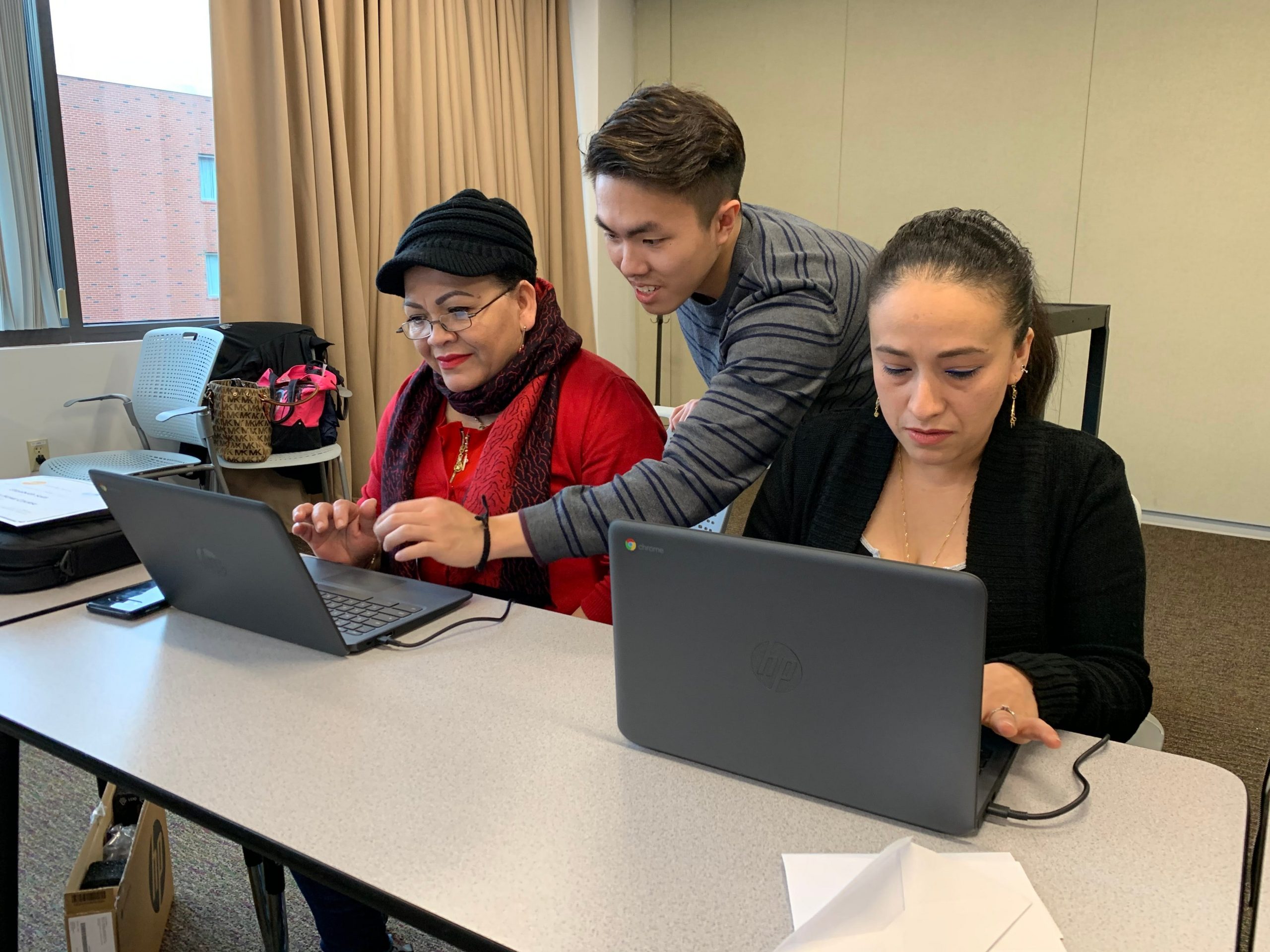

Digital-literacy education should be tailored to individual needs

Tech Goes Home

Quantifying the problem of digital inequity in Boston is difficult. According to the US Census Bureau's American Community Survey, about 15% of Boston households don't have internet access - but, the number is most likely much higher, Noyes said, since the data is derived from surveys, which often leave out marginalized communities.

The biggest issue, besides many people not having access to tech or internet, is that many others often lack the skills to use technology.

Tech Goes Home partners with community programs, like libraries, schools, churches, and homeless shelters that serve hard-to-reach communities, and trains their staff to host 15-hour digital-literacy courses.

Each course is tailored to the needs and interests of the attendees. For example, classes for people who are unemployed focus on finding a job, and those for older people focus on health or communication tools. Everyone who takes a class receives a free laptop and a year of free internet service.

The program targets low-income residents. Noyes said about 90% of the people TGH serves are considered "very low income" by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, 85% are people of color, 50% are English-language learners, and about 60% are women. Since 2010, about 40,000 people have gone through TGH's programs.

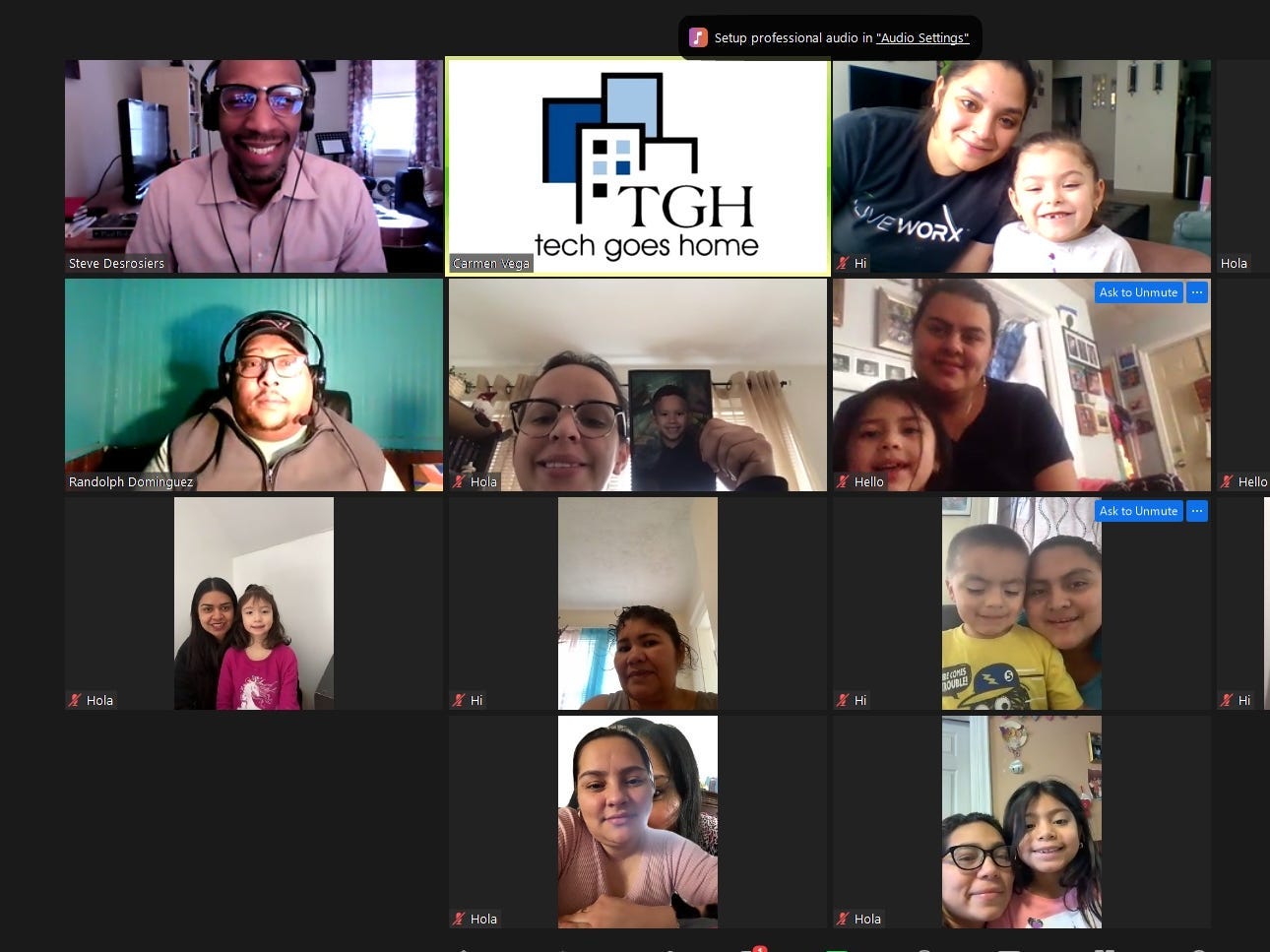

Taking digital-literacy learning online amid the pandemic

Tech Goes Home

TGH's programming had always been in person - until the pandemic hit. By summer 2020, Noyes said his team had created a distance-learning program, but setting up an online program for people who lack digital-literacy skills and internet connectivity was a challenge.

Pre-pandemic, attendees received their computers after completing the course. In shifting to online classes, Noyes said they decided to send a laptop and a WiFi hotspot to people's homes so they could get online. At first, he said they worried people might just take the computer and not complete the course, but that didn't happen.

"Our graduation rate was 92%, pre-pandemic," he said. "During the pandemic, our graduation rate was 92%. People stayed involved."

The courses were held via Zoom, and while many people experienced Zoom fatigue over the past 18 months, Noyes said for the people TGH serves, it was a lifeline. Many had lost their jobs during the pandemic and weren't going to the places they normally would.

"This was an opportunity for them to see members of their community that they wouldn't be able to see," he said, adding that he enjoyed popping into the classes. "People were so happy to see each other. It was something special beyond learning."

Keeping the momentum up in Boston

This month, Mayor Kim Janey and the city's Department of Innovation and Technology commissioned a study on the availability, cost, and equity of broadband in Boston to identify service opportunities and disparities by neighborhood.

"We're showing that everything we do is impacted by digital equity," Noyes said. "If you go to find a place to live, you go online. To find a job, you go online. You want to get vaccinated, you go online. If you don't have access to that world, think of how many opportunities you're denied."

Internet access for low-income communities is just the first step in closing the digital divide, Noyes said, and he believes the city will eventually be able to offer that. Now more organizations are taking a look at the problem of digital equity. Noyes just hopes the momentum continues.